The Future of Wireless Service and Systems

The Future of Wireless Service and Systems

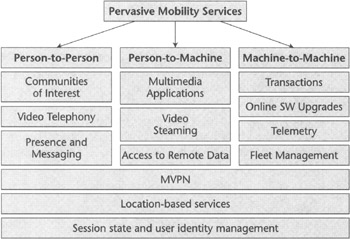

Let's consider possible service scenarios, depicted in Figure 9.3, as well as the players and technologies that would enable them. A critical requirement of Internet-based services is the ability to deliver an environment the user feels comfortable with and is attracted to. This environment may be created via human-machine interaction: a well-defined graphical user interface (GUI), easy-to-use service options, interface customization, and self-adaptation to customer usage profiles. It may also involve hosting communities of interest, where groups of individuals can share emotions, experiences, ideas, and information. This requirement must be satisfied by person-to-person and person-to-machine data services offered by wireless systems, but of course, not by machine-to-machine applications. In this section we examine these aspects of future wireless systems, as well as new services offered by some new types of carriers entering the market, such as MVNOs and WLAN access service providers.

Figure 9.3: Future mobile services examples.

Figure 9.3: Future mobile services examples.

Person-to-Person Services

In traditional telephony, interactions between two or more human users of the service usually occurred after some mutual knowledge had been established and after the exchange of phone numbers via channels other than the telephone network itself. We refer to this as an "out-of-band method." This model is still valid today, with the exception of consumer-to-business (e.g., free phone calls, dialing of a number looked up in yellow pages directories) and business-to-consumer (e.g., telemarketing applications and customers surveys, which are not frequent in mobile telephony, other than from service providers themselves) applications where only one party knows the other in advance. Dating services removed the need to exchange out-of-band phone numbers, although some of them rely on SMS-based exchange of information.

In next-generation person-to-person services, phone numbers will cease to be the only identity through which users will be known. More likely, users will subscribe to communities using a public identity. They will establish social contacts with members of these communities, creating a comfortable environment and fostering demand for other mobile telecommunication services. For instance, a user may create a virtual community involving all of his family members for the purpose of exchanging text messages, images, short videos, and voice conversations. Corporate communities of interest will also be set up to offer messaging and information dissemination services. Information distributed within these corporate communities may be privileged or restricted. Community membership rights will be critical in this type of environment. Managed community services may become an important part of a wireless carrier business, frequently bundled with managed VPN for security and privacy.

Community members may be alerted via an icon-based interface when the others are reachable. In this scenario, phone calls will be placed only when another user is available; otherwise, other media-based messages can be left in users' mailboxes. Users will be able to selectively signal their availability to other members or member subsets depending on, for example, the time of day and business status. In this approach, a set of addresses would no longer be stored locally in a phone book; rather, a list of the "friends" or identities organized on a per-community basis would be stored in the network. Of course, this does not mean the death of the phone number, since the old-style phone book is likely to exist in order to place and receive phone calls. Instead, this model offers new ways to let individuals interact through mobile and nonmobile devices. This will significantly increase the amount of information exchanged via other media [such as picture messaging, already being rolled out in Europe via Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS)], and consequently the service provider's revenues.

Another important aspect of this new user-interaction model is the entity acting as the communities' host. Users may in fact be able to subscribe to communities hosted by parties other than the wireless service provider. However, the wireless service provider may potentially offer much more added value that would encourage customers to use communities hosted in its environment, since the wireless carrier has the opportunity to integrate in its environment other valuable services such as location-based information, push-to-talk voice services, session related information and single sign on. Thus, communities hosting by wireless providers can result very competitive and highly differentiated with respect to what the third parties may offer. Third parties willing to offer similar user experience might eventually be forced to partner with the wireless carriers, becoming one of the partner ASPs, for example.

Another service that promises to become a mainstream revenue generator in 3G systems is video telephony. However, while it would significantly enhance interpersonal communication, pricing issues may prohibit its success. Historically, video telephony has not been successful in the wireline, which seems to be the case even now, when many households and businesses can be easily equipped for inexpensive high-speed communications. Perhaps mobility and the need to associate a voice with a face among the individuals involved in a conversation may prove to foster this service, along with the ability to distribute an image of a current location at the time the video-enhanced speech session is placed.

Initially, at least, community access should not be bound to any charge other than a modest flat subscription fee, in order to foster the growth of the services associated to them. As with many other telecommunication services, communities suffer from network externality, where the value of the service itself is bound to the existence of other subscribers using the same service. Access barriers should be minimized in order to attract users to communities where they can use a plethora of services, which together will constitute a significant revenue stream. As mentioned, the creation of communities and the ability to manage "friends" lists and customized user profiles within them is imperative for customer retention and attraction, since the social aspects of such unique services will have a significant effect on the users. Wireless carriers will therefore most likely be encouraged to create mutually incompatible communities hosting environments, similar to the instant messenger services offered by players such as MSN, Yahoo, and AOL.

Person-to-Machine Services

Unlike person-to-person services, a person-to-machine service offered by wireless carriers does not entail synchronous, real-time interaction between humans. For this set of services, humans interact with hosts of data or multimedia applications, encompassing entertainment, information retrieval, and transactional applications. These services are based on the availability of "content" that humans are willing to access.

Users belonging to virtual communities can themselves generate some of the content, via person-to-person exchange of images, short movies, text, and Web content. Still, it is expected that most of the content will be provided by partners and hosted either on partners' networks or on wireless carrier facilities. This will require the use of MVPNs to enforce service exclusivity and protect against denial-of-service attacks and unauthorized access.

In this book, the term content has a broad definition; it applies to everything a user may experience by interacting with a person or a machine, when the machine does not act as a mediator between two human beings interacting in real time. For instance, a chat session, which still is mediated by an application server, is not content, but a Web page created by a user of a community or that is presented to a user during a travel reservation session or a weather forecast page consultation is. Success of content-based services in person-to-machine scenarios, as in the person-to-person case, depends highly on the user-friendliness and the clarity of language used to interact with the user. Very often, to the chagrin of the service provider, this detail is forgotten when these services are designed.

Person-to-machine services are used in today's networks in information products such as traffic conditions reports and interactive voice-response systems used to retrieve account status information or to update information, such as credit card number, in subscribers' profiles. Usage of these services is not yet widespread, since the majority of users still prefer direct operator assistance to the sometimes difficult-to-understand menu options or voice-response systems that fail to correctly guide the user. Clearly, machines are better accessed through point-and-click-based interfaces rather than via voice-based interaction, although there are indeed some applications based on Voice XML, a markup language similar to those used to create Web pages that is optimized for voice-based content navigation and collects voice input and executes voice commands. When mobile devices become equipped with enhanced graphics and point-and-select input, better human-machine interaction will be possible, leading to "enhanced user experience" based interfaces. One of the issues that must be considered is how the user inputs the information while interacting with machines. With the small form factor mobile devices, it is unlikely the user could easily input text, which requires a minimum amount of necessary text entry on a user-friendly interface.

From our view, person-to-machine applications are poised for success with both wireless subscribers and service providers for a number of reasons. First, these services are not expected to suffer from network externality, so they may be the first to be requested while community-based and other novel kinds of person-to-person services are still ramping up. Second, timely access to up-to-date financial information, weather forecasts, airport schedule and flight status, traffic reports, or location-based entertainment typically matches the anytime-available capabilities of information access media such as mobile devices, and the likelihood that the user is on the move while requiring this information is pretty high. Additionally, most of these services deliver value at well-defined time intervals, when the desired information is delivered or a transaction is complete, and it is therefore possible to define a fair price per application level events and avoid charging on a per-byte basis. Customers may be required to directly pay the wireless carrier, or the endpoints of the transaction may be required to pay a commission to the wireless carrier, or both. For instance, a bank offering mobile banking services may charge customers a fee per transaction while on the move. Or the bank may offer the services for free as a way to attract customers and then have a framework agreement with a wireless provider to deliver the service for a flat fee or a per-event fee.

Communities may become a vehicle for human-machine services. A community may be entitled to receive some information from the machine reserved just for its members; for example, a community may be defined as a group of customers of a big banking institution and any member may be addressed with news from the bank or welcome to interact with virtual members, which are simply machines offering help desk service or acting as virtual attendants.

Familiar Internet access service is another good example of human-machine application. In the near future it is most likely to be bundled with the wireless data service offer and not likely to generate significant revenues based on per-traffic-volume fees. On the other hand, wireless access may foster a breed of new services on the Internet itself, and these services may in turn use information derived by accessing data available from interfaces wireless providers offer to third parties, such as via OSA gateways or Web interfaces.

| Note |

Open Services Architecture (OSA) is standardized by 3GPP in the TSG CN WG5 group, which defines a set of APIs that can be used to invoke services wireless carriers allow third parties to access at OSA gateways. Such services may include, for instance, session status information, user availability and location, and billing and accounting. The delivery of such information to third parties will constitute a revenue stream. |

Another application that is thought by many as a potential driver of 3G services is video streaming—not unlike video telephony. In general, we expect video streaming to be offered in the form of short-duration clips that satisfy users' curiosity about a news item or events, or about the user's current location, such as historical news, cultural information, and tourist information. The delivery of lengthy entertainment video or entertainment clips that may be easily available at home via broadband access or cable service cannot realistically be expected in the foreseeable future mainly for the bandwidth limitations and other arguably obvious reasons such as device screen size and short battery life.

Let's now consider a hypothetical real-life person-to-machine service scenario. John and Alice arrive at their travel destination one evening without a hotel reservation. They book it swiftly via a location-based hotel directory service, check in, and decide they are ready for a night out at the cinema. They have already previewed a movie in the car before arriving at the hotel. They invoke a location-based service in their mobile device to decide what local cinema to pick among those offering the movie they are interested in. They check availability, select the seats, and buy the tickets on the way to the cinema. To enter the cinema, they just need to point their mobile device to a Bluetooth-enabled checkpoint that exchanges authorization information with their device, equipped with the subscriber's digital certificate that was used to provide the user identity when the ticket was sold. After watching the movie, they are reminded about a prearranged get-together with friends by their mobile calendaring application, so they send them a message showing their rendezvous point on the map, obtained from a simple request to a location-based service. They eventually go out for a late-night dinner at a restaurant suggested by their friends (not via an online service this time).

Even this simple, nonbusiness related example illustrates how many services can be provided to a customer and how many revenue opportunities can be made available to an operator if at least some of the new technologies we described see mass deployment. One thing that carriers must avoid is creating the expectation that all of these services are free, which has worked fairly well with SMS (that is, SMS customer expectation about the service fee were set before service introduction and accepted by the consumers), and as such it may be the same case for other wireless data services.

Machine-to-Machine Services

Machine-to-machine is to us the most interesting and unexplored type of mobile service. So far, most of the services offered by mobile operators almost always involved a human user at one of the endpoints of the communication sessions. With the mass deployment of wireless data, this paradigm can now be shifted, and revenue streams from machine-to-machine interaction can start contributing to operator's bottom line.

The space for this kind of application is very wide and largely untapped. Examples include letting mobile manufacturers remotely upgrade handset software via the wireless interface, using the mobile as an authentication and authorization token for payment purposes instead of the traditional credit card, or bundling wireless terminal capabilities to a machine and letting it interact with centralized information or computing resources. At the early stages this will be possible only on a small scale, and only for machines for which the marginal cost of bundling a mobile terminal does not add much to the final price of the device. Therefore, such services may be confined to specialized devices. Later, as the unit terminal cost drops, this may become more common for generic consumer devices.

Another example, telemetry applications, involves remote monitoring of devices and events. This was one of the most commonly quoted applications—although perhaps not as commonly used—in the early wireless data systems. With the advent of location-based services, new types of fleet management applications can be expected to appear as an extension and enhancement for the existing telemetry services. This might require the integration of the application in corporate network environments, thus associating the location-based application with a community-based service where the community member is a vehicle belonging to the fleet, all supported over an MVPN associated with the company that owns the fleet. Possible customers for such services include transportation companies and radio taxi services to convert to cellular-data-systems-based car booking and assignment (although at the end the human will use information exchanged by the in-car computer system and the centralized reservation system, there is a high degree of human independence in this service). Other applications may include the backup line provisioning for mission-critical environments in case of failure of a wireline link on some access routers, as well as remote monitoring.