Security Layers

Despite the best efforts of social reformers, humans tend to organize things into layers when it comes to management. There was a fashion in the 1980s for start-up companies to be organized on a communal basis in which everyone was equally important and all meetings were open. Nice touch, but the reality is that every one of those companies that grew beyond a handful of people coalesced into a layer management structure very rapidly. People must have a limited scope of control in order to be effective. Therefore, if the organization is to scale up in size, you have to allow specialization of function and different levels of policy control.

So what's this got to do with Wi-Fi LANs? Well, in some ways, WEP was like the trendy start-up. All the security issues were bundled into a single simple package of measures and all were defined within a single standard. Quite distinct from the technical failings of WEP, this resulted in a solution that could not be scaled beyond a handful of devices. Some functions, such as encryption, are very local affairs and are only relevant to the Wi-Fi LAN hardware that is doing the actual communication. But other issues, in particular the decisions about who is allowed to access the network, have very wide importance and need to be consistent across an entire network.

For these reasons, it is necessary to identify and implement management layers in the security solution. This can be seen in the passport control system that involves layers of government from the immigration officer at the airport desk, through the passport administration center and up to the immigration policy decision makers in the Cabinet.

In the context of wireless LAN security, three layers are clearly identified. In fact, these layers are not specific to wireless LAN, but apply to any LAN-related security system. An advantage to choosing this layered model is that the RSN solution can fit into existing security architectures that have been deployed for other purposes and also leverage the standards that already exist.

The three layers of security are:

Wireless LAN layer

Access control layer

Authentication layer

The wireless LAN layer is the worker. It is the job of this layer to deal with raw communications, advertising capabilities and accepting applications to join the network. The wireless LAN layer is also responsible for encrypting and decrypting the actual data once a security context is established.

The access control layer is the middle manager. It is the job of this layer to manage the security context. It must stop any data passing to or from an enemy. Here an "enemy" is defined as anyone who does not have a current security context established. The access control layer is fickle, and you can immediately change your status from enemy to friend when authentications occur and the security context is established. The access control layer talks to the authentication layer to know when it may open the security context and it participates in creating the associated temporal keys.

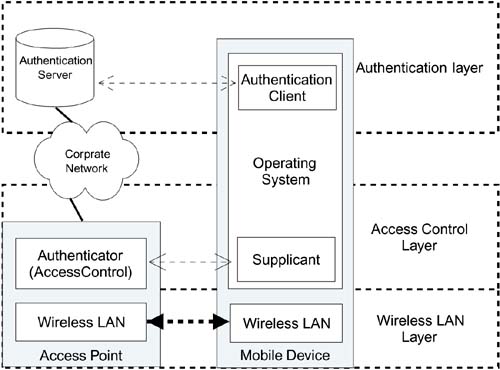

The most senior layer is the authentication layer. At this layer the policy decisions are made and proofs of identity are accepted (or rejected). In effect the authentication layer has power of veto over anyone who wants to join the LAN and delegates power to the access control layer once it approves the application for someone to join the LAN. The wireless LAN layer obviously resides in the wireless device contained in the access point. Usually the access control layer resides completely in the access point. Although in small systems the authentication layer might be in the access point also, in larger systems, the authentication layer is usually implemented in an authentication server quite separate from the access points. This ability to centralize the authentication server provides a scalable way to manage the user database. In other words, it solves the key management problems of WEP and makes it easier to integrate Wi-Fi LANs into the overall corporate security management system.

On a mobile station, there are similar layers. Typically, the wireless LAN layer is implemented in the Wi-Fi adapter card and its associated software drivers. The access control and authentication services may be implemented in the operating system or, for older systems, in the application level software provided by the manufacturer. Remember that it is very important that the mobile device also authenticates the network to ensure that it is not joining a fake network set up by an attacker. Figure 7.3 shows the relationship of all the layers and a typical example of where the layers operate. Note that in the figure "supplicant" refers to the part of the mobile device's operating system that makes the request to join the wireless LAN.

Figure 7.3. Relationship of Layers

How the Layers Are Implemented

The IEEE 802.11 standard covers only wireless LANs, and the standards group is not chartered to define the behavior of systems outside this specific area. This presents a problem when designing systems that need the cooperation of various layers to work. This is one of the reasons that the original WEP standard tried to define all the security issues within the wireless LAN layer. When designing RSN, the standards task group avoided this problem by referencing existing standards developed outside IEEE 802.11, especially for the access control and authentication layers. In the few cases in which these other standards needed to be modified, the IEEE 802.11i group contacted the other relevant standards and requested changes to be made.

There seemed to be a perfect existing candidate for the access control layer. As early work progressed on the security standard, another standards group, IEEE 802.1X, was putting the finishing touches on a standard designed specifically to deal with access control (IEEE, 2001) IEEE 802.1X was selected as most appropriate for access control with (almost) universal approval, although this, too, had to be modified later to meet all the needs of security identified by the TGi group.

The authentication layer was much more problematic. The difficulty here was that there are many possible candidates. The purpose of having the authentication done by this upper layer was so that corporations could integrate the authentication into their existing security approach. But it turns out that there are quite a few different methods in use. And, of course, each corporation believes that the approach it is using is the best one.

In the end the decision was made that IEEE 802.11i would not specify any mandatory upper-layer authentication method, but that the RSN approach would be designed in such a way that any of the existing "good" methods could be applied. The word "good" here underlines the fact that the standard places requirements on the security capabilities of acceptable methods. For example, all methods must support mutual authentication.

In the following chapters, we look in more detail at the way in which the authentication, access control, and wireless LAN layers are implemented and how they interact. Because there are layers and different standards are employed at each layer, it might seem that RSN is very complicated. There is no doubt that it is a formidable task to read all the standards that are incorporated directly or by reference. What we intend to achieve in this book is an overview of the relevant parts of each standard so you don't need to undertake this task. Then those standards should be much more accessible should you choose to dive in.