Notification Services

|

Notification Services is one of those products that does what it says: It provides a means of notifying a user that an event has occurred in a database. The system uses several components to accomplish this goal, from the databases that store data about the events to the control files and databases that shepherd the process. Let's begin by examining a few applications for Notification Services and how you can distribute them. The most obvious uses involve applications that require immediate feedback for a user. These include changes in prices, levels, inventory, and any other information that is time sensitive. Other uses for Notification Services might not be as obvious. Marketing studies show that clients are most frustrated when they feel that a company is not responsive. You can code your applications to notify a customer as to which stage an order is in, such as when it is complete, when it leaves the building, or any other action that makes a change to a status code in a database. You can also set up a notification that an order was received and when it was placed. For the system administrator, you can use Notification Services to help reactively manage your systems. Normally, a reactive mode of managing anything in IT is a bad idea, but using Notification Services you can build in the look-ahead logic so that a server watches objects (like backups or other maintenance) for you and can alert you when a threshold is reached. So just what is Notification Services? It is an infrastructure within SQL Server 2005 that involves a service, instances, and applications, and a set of programs your developers create to interface with the system. In this chapter, I focus on the Notification Services instances and applications. The easiest way to create the system is programmatically using notification management objects (NMOs). You can find several examples of this type of programming if you installed the sample and applications on your server. You can also create and manage Notification Services using the native tools within SQL Server 2005 using XML files. We take a look at the structure of these files and examine the results of its implementation so that you can see how to manage and maintain it. In practice, most applications are coded using NMOs, but you can always create the instance and application XML files with an Export from the Object Explorer right-click menu in SQL Server Management Studio. Notification Services ArchitectureThere is a lot of excellent information in Books Online regarding Notification Services, but it is not arranged in a holistic view of the system. There is a good reason for that. Notification Services uses several components within the SQL Server 2005 platform to accomplish its goals. In addition to all the capabilities that Microsoft delivers, your developers can extend every part of the system with custom programs and interfaces. To get a picture of how this all fits together, let's start at the back of the system and work forward to the user who receives the notification. Because Notification Services has so many components, I am going to cover it three times. In the first, I give you a broad overview, then I explain it again with a little more detail, and then I cover the various basic components by explaining the Instance Configuration File (ICF) and the Application Definition File (ADF). Even with all of this information, you are only seeing a quick overview of this topic.

In Notification Services, several terms are used that already have meanings within SQL Server, such as instance, publisher, subscriber, and so forth. In this chapter, pay close attention to the definitions that Notification Services uses for these common terms. At the back of the process is SQL Server 2005, which stores the data the users need to see and all of the metadata that Notification Services requires to operate. On top of SQL Server is the NSServer.exe program, which runs all of the instances, which make up the notifications for the users. To create these instances, you have two options: Your developers can create them with programs that use NMOs, or you can create them using an XML document called an ICF. With an instance created, you create one or more Notification Services applications within it that listen for events, which are changes that your users are interested in knowing about. Events might involve database activities but also can track changes in Analysis Services, files on a file system, and other activities. These events are matched with subscriptions, which are sent to the subscribers (users) over various protocols to devices such as cell phones or e-mail. Once again, your developers can create Notification Services applications using NMOs or you can create them with an XML document called an ADF detailing the parts of the application. If you create the instances and applications using XML files, you import them using SQL Server Management Studio or the NSControl.exe command-line program. That is the first overview, which leaves out quite a bit of detail. Let's examine the process a bit further. After the instance and applications are created and running, the instance uses a program called NSServer.exe that runs in the background watching for events using an event provider. Event providers watch for database changes, file system changes, and other events. It then applies matching rules to pair up the subscriptions and the events and then sends the data on to a provider. A provider is a piece of software that receives the data and formats it for delivery. Providers are called by the application, and a generator matches up subscriptions to the events. Subscriptions are groups of data that a subscriber (the user) cares about. Notification Services populates the entire subscription, which is read by a distributor. Distributors use special-delivery services to talk not only to other databases but to file systems, e-mail and telephones, and any other kind of communication system your developers create. The distributor formats the output using a content formatter and then sends it on to the delivery protocol provider, which can send data over SMTP, HTTP, and SMS. The subscriber receives the data in that format, over that protocol. As the third explanation of the process, let's take an even deeper look at two of the primary components that you will work with: the ICF and the ADF. Using these XML files, you set up the instances and applications that enable your developers to create a complete Notification Services system. All the pieces I have been talking about begin to come together as you examine these files. Instances and the Instance Configuration FileAn instance of Notification Services is a collection of applications that run as a unit on a SQL Server. You can have one or more instances on a single SQL Server. You can create an instance programmatically using NMOs or by using SQL Server Management Studio and an XML file called an ICF. That is the approach I take here.

The ICF contains the name of the instance, a database for its control, the name of the applications that can talk to the instance, and encryption and delivery information. You can also place a version stamp in the file, which I recommend for production applications. The format for the file is detailed in Books Online under the topic "Instance Configuration File Reference." I display the minimal ICF file here so that we can talk a little about the parts that are required. In a moment, I show you the results of importing an ICF file into the database using SQL Server Management Studio. If you want a useful example of Notification Services, it is best to consult the examples from Microsoft, if you installed them. Setting up a complete system with an interface and databases and explaining it all would take up much more than a single chapter and would involve you in parts of the system that a DBA does not normally handle. I do recommend you use the examples, however, because they will shortcut all the development for you and allow you to concentrate on managing a Notification Services system. Here is the minimal version that you need to fill out for a basic instance. Each section is commented out ( <! comment >) so that we can more easily discuss it: <?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <NotificationServicesinstance xmlns:xsd="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns="http://www.microsoft.com/MicrosoftNotificationServices /ConfigurationFileSchema"> <! Notification Services instance Name > <instanceName></instanceName> <! Database Engine instance > <SqlServerSystem></SqlServerSystem> <! Applications > <Applications> <Application> <ApplicationName></ApplicationName> <BaseDirectoryPath></BaseDirectoryPath> <ApplicationDefinitionFilePath></ApplicationDefinitionFilePath > </Application> </Applications> <! Delivery Channels > <DeliveryChannels> <DeliveryChannel> <DeliveryChannelName></DeliveryChannelName> <ProtocolName></ProtocolName> </DeliveryChannel> </DeliveryChannels> </NotificationServicesinstance> It looks like there is a lot going on here, but it is actually quite easy to follow. The first five lines of the file represent an XML header, which details what the file is and how it will be used. That does not change for any of your instances. The rest of the sections control the creation of the instance, similar to the old .INI files of earlier Windows programs. <! Notification Services instance Name >The first section, specified in the <instanceName> element, sets the instance name for the system as well as the service it creates to run this instance. From here on out, the applications and other parts of this notification system's grouping will refer to this name. I usually keep these short and as descriptive as possible. The instance Name becomes the name of the service that runs in the operating system, prefaced by NS$. For example, the following entry creates a service called NS$AWInventory: <instanceName>AWInventory</instanceName> <! Database Engine instance >The <SqlServerSystem> element sets the name of the SQL Server instance (no relation to the Notification Services instance set up with this file) where the Notification Services instance will run. It is the name of the server where you want the service to run. <! Applications >Each instance holds one or more applications that can talk to it. The <Applications> element is a parent element that contains other information that relates to the applications that will run under this instance. In effect, it is pointing to the ADF that you will also need to create prior to importing the instance using the ICF.

If you try to import an ICF before the ADF is complete, you will get an error. This section includes the name of the application and its location and name on the hard drive. You can store these files in a shared folder, as long as the SQL Server and service accounts have access to it.

In this example, I create only one application for the instance, but you can have as many as the resources for your system allows. It is best to plan out the entire system before you begin this process so that the instances are broken out logically to contain the applications that make the most sense to group together. The first child element in the <Applications> tag is <Application>, which is another parent tag. You repeat this element for each application that the instance will host. Within that parent element is the <ApplicationName> element, which sets the name of that particular application. Each application needs a directory to store its ADF. This file, which I create in a moment, holds the same kind of information created for the instance but sets up the application. The next element, <ApplicationDefinitionFilePath>, sets the name of the ADF file. If you store only the filename here, the file needs to be stored directly in the BaseDirectoryPath location. The reason you have two elements available is because in actual production, you will normally have several applications that run on a single instance. You want to keep these applications separate so that various developers can have the access they need to work with only the applications they are assigned to. Keeping the applications in separate directories allows you a greater level of security. <! Delivery Channels >The instance controls how the system communicates with the outside world. The first parent element, called <DeliveryChannels>, begins the section describing all the ways that this instance can communicate. You open the delivery method with the <DeliveryChannel> element, and then type in the <DeliveryChannelName> element to have the type you want, from e-mail to file. Within that instruction, you need to specify the protocol the channel will use. You do that with the value of the <ProtocolName> element. There are lots of ways to send information, each with its own protocol settings. So that we can maintain the overview process here, I will direct you to Books Online using the topic search I mentioned earlier to learn about the various methods you have available. With all of the basic elements defined, we need to create the ADF. Applications and the Application Definition FileOne or more applications are contained within a single instance of Notification Services. When you create an application, you will also create or specify a database that stores the events, the subscriptions, notification data, and other application metadata about the application. If you do not have a database, you can have the XML file (or the NMO program) create one for you. Once again, we will look at a basic XML file and examine the elements it contains: <?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8" ?> <Application xmlns:xsd="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns="http://www.microsoft.com/MicrosoftNotificationServices /ApplicationDefinitionFileSchema"> <! Version > <! History > <! Database Definition > <! Event Classes > <! Subscription Classes > <SubscriptionClasses></SubscriptionClasses> <! Notification Classes > <NotificationClasses></NotificationClasses> <! Event Providers > <! Generator Settings > <Generator> <SystemName>%SystemName%</SystemName> </Generator> <! Distributor Settings > <Distributors> <Distributor> <SystemName>%SystemName%</SystemName> </Distributor> </Distributors> <! Application Execution Settings > <! Important: At minimum, you should define a vacuuming schedule and turn off some or all distributor logging. > </Application> This file has quite a few subelements, so once again I recommend that you look up the topic in Books Online using the search topic "Application Definition File Reference." There you will find all of these elements hyperlinked, in alphabetic order. Using this minimal template and those search results, you can quickly build the file you want. In this minimal file, the first four lines set the header for the XML file and tell SQL Server 2005 how to handle it. <! Version >The first section here is the <Version> element. Within that are various child elements that set a version number and build. The <Version> element is optional, but I normally include it so that I can track where I am in the build process. It is a good habit to get into. <! History >The History section is similar to the Version section, in that it provides tracking data for your system. You can include data here to track what changes you have made to the ADF. <! Database Definition >In the <Database Definition> elements, you set the name, schema, and physical structures for the application. If you do not provide one, the system creates a database using the defaults for the server. In a moment, I create a Notification Services application and show you the types of things that end up in this database. <! Event Classes >It is in the Event Classes section that things really become interesting. In this section, beginning with the <EventClasses> parent element, you set up one or more <EventClass> elements that define what events the system responds to. <! Subscription Classes >In the Subscription Classes section, using the parent tag of <SubscriptionClasses>, you set up one or more subscriptions for the application using <SubscriptionClass> elements. Here you describe the name, the schema for the subscription, any indexes you want on the tables, and event and schedule rules. All of these elements set up how often the events are captured and what can be subscribed to. <! Notification Classes >Using the <NotificationClasses> parent tag in this section, you set up one or more notifications for the application using <NotificationClass> elements. These elements define where your application stores the notifications, what filter is used to format them, and what protocols the transport uses. You can also set whether the notifications are sent one at a time or if they use a "digest," which groups them all together to be sent at the end of a specified period. All of these settings are similar to what you will see in a newsgroup; and if you think about it that way, you will have the concept. <! Event Providers >As I explained earlier, an event is a change in data that you care about. For instance, a stock price change or a project change would be an event. Microsoft delivers several of these with SQL Server 2005, and you can also write your own. Here are a few of the event providers that your system can use.

The most prevalent event that I have seen used is the SQL Server event. This allows you to watch a table for changes and deliver the information to a user via a subscription. Each of the event types has specific elements they require to be able to process them. <! Generator Settings >The generator is the component within Notification Services that matches changes in data (events) to those who should learn about the changes (subscribers). It runs in the background on your server using the NSServer.exe program. In this section, you use elements to define the name of the system that will act as the generator and set the amount of threads it will use. <! Distributor Settings >The distributor is the component within Notification Services that formats and sends the data. You can store the distributor on one or more servers to help balance the load on your system. You use elements in this section to set the name of the distributor, the threads it uses, and an optional duration setting. <! Application Execution Settings >In this section, you set up all of the information around the processing of your events, such as limiting the amount of time that is spent on a particular task as well as the order in which applications are processed. An important element to set is the <Vacuum> value, which sets how often the cleanup process runs. With all of those components in mind, let's take a look at how all of it fits together within the framework of a complete application. I have a single application that I plan to set up to watch an inventory level. I have created the ICF and the ADF and placed them in a directory on my local test system. I will import those into my instance of SQL Server 2005. Installing the Instance and Creating the ApplicationIn Figure 7-1, I have opened SQL Server Management Studio and right-clicked the Notification Services object in the Object Explorer. Figure 7-1.[View full size image]

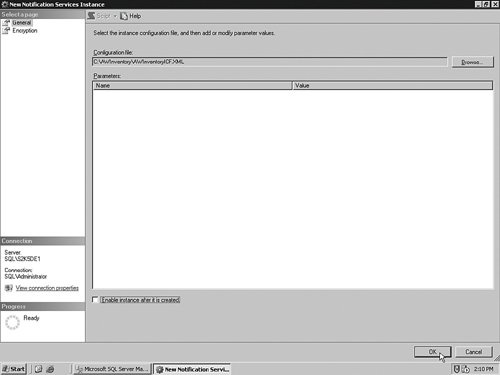

Within that panel, I specify the location of the ICF, as shown in Figure 7-2. Figure 7-2.[View full size image]

With that set, I click the OK button to process the file. My system shows the screen in Figure 7-3 while it processes. Figure 7-3.[View full size image]

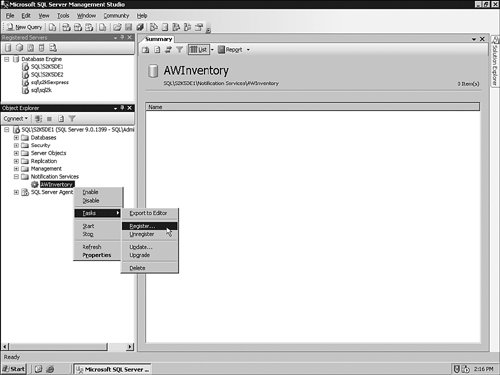

Now I will enable the system by right-clicking it in the Object Explorer again. This process sets the distributors, generators, and subscriptions for the system. You can see that in Figure 7-4. Figure 7-4.[View full size image]

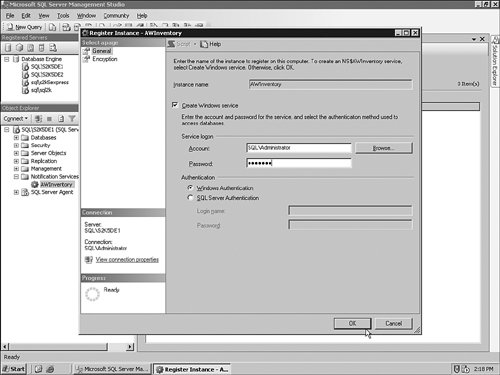

When that process completes, I right-click the service and select Tasks,… and then Register from the menu that appears, as shown in Figure 7-5. This brings up a panel where I create the service, set the authorization for the service, and set how the service will access the database. You can see that in Figure 7-6. I receive feedback that shows that the system is creating registry entries, creating the service, and adding new performance counters. With all that complete, I again right-click the name of the service and select Start from the menu that appears. After confirming that I want the system to start, the databases I specified in the ICF (AWInventoryNSMain) and the ADF (NSMetaData) are created, and the service starts. Figure 7-5.[View full size image]

Figure 7-6.[View full size image]

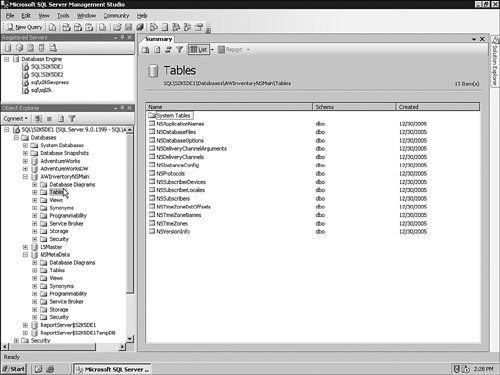

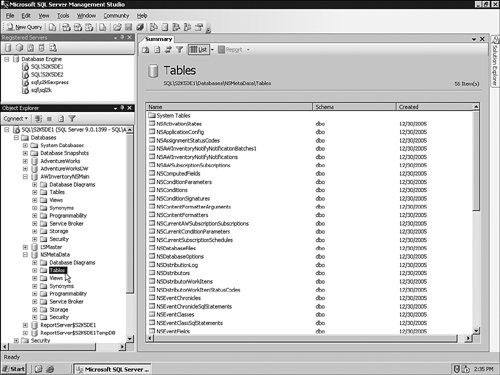

Figure 7-7 shows a list of the tables within the instance database called AWInventoryNSMain. Figure 7-7.[View full size image]

This database contains the elements I explained earlier within the ICF document. There are a few other metadata tables here, especially involving the time settings such as time zone and locales. The tables in the application database called NSMetaData also contain the elements I explained in the ADF and other metadata. You can see all of that in Figure 7-8. The service reads these databases and accesses the information, ready for the client programs to subscribe, similar to what I explained for replication. Figure 7-8.[View full size image]

SecurityThere are two parts to the security of your Notification Services system. The first is to secure the locations where the ICFs and ADFs are located. The reason you want these files secure is that those who can access them can change them to reflect more data in the Events section than you might want. The small files I described earlier are not representative of what you create in a production environment. The production files are much larger, so you might miss the addition of a new event or a change to a current one. After you have your instance running, you can alter it later by re-importing the ICF and ADF. That is where the danger comes in on leaving these areas unsecured. If your developers are using NMOs to code the application rather than the control files, this is less of an issue. The second part of securing the system is against the subscription data. To secure this data, you simply use Windows accounts or SQL Server accounts. Monitoring and Performance TuningNotification Services can be used on servers that scale up, and they can also be used on a cluster. Another method for tuning the application is to spread it out onto multiple servers, including the generators and other parts of the application. That is why it is important to plan out the system ahead of time. You can monitor a Notification Services system in SQL Server Management Studio by right-clicking the instance you are interested in and selecting the Properties item. Once inside, click the Applications item in the left pane, and in the Components for that application, check the Status column, as shown in Figure 7-9. Figure 7-9.[View full size image]

You can also check the Subscriber status from this resource box. Another monitoring tool is a suite of Performance Monitor objects and counters that you can access from the System Monitor in Windows, as you can see in Figure 7-10. Figure 7-10.[View full size image]

You can monitor all parts of the system based on what you are interested in examining, from the subscriber subsystem to the collection methods. |