From Illustrator to the Web

From Illustrator to the Web

When you create a graphic in a pixel-based program, such as Photoshop, you have to decide how big you want the graphic to be from the very start. If you want to enlarge the graphic, you add pixels; if you want to make the graphic smaller, you throw away pixels. Either way, you get a blurry, lower-quality image. But with Illustrator, you don’t have these problems. Even though you ultimately create pixel-based graphics, your graphics don’t become pixel-based until you save or export them. You can save the Illustrator file many times at different sizes, and each one will be at the best possible quality!

The differences between creating for the Web and creating for print happen when you save your graphic. Whenever you create artwork in Illustrator for the Web, you work just as always. The key difference is in how you save your work after you create it. The only other difference that you may find is in the color choices whenever you create a graphic for the GIF file format. (More on that in a moment.) Otherwise, the creative processes for Web and print are identical.

Because you view Web graphics on-screen, you have a much better idea of how they will look after you put them on a Web site than you would if you were going to print them. Colors on-screen (and on the Web, which is always displayed on a screen) consist of red, green, and blue (RGB) pixel combinations. So if you create graphics just for the Web, RGB documents (for more on RGB see Chapter 1) are your best bet. If you create things for both screen and print, RGB gives you the greatest flexibility.

Using Web colors only

Suppose that you’re in a room full of Web designers and you hear them talk about Web-safe color space and the Web palette. You look around discreetly. A dapper man in a dark suit steps out from behind the potted plant and tells you, “You’re traveling through another dimension . . .” and a weird piano riff starts to play. . . .

Granted, Web design can seem pretty weird. At least the number of colors is relatively small. Web-safe color refers to a set of 216 colors that look the same in all Web browsers and on all computer platforms. If you’ve been creating for print for any length of time, you may be used to using an almost unlimited range of colors. A mere 216 colors may seem limited at first, but there’s method in the madness.

One key benefit of the GIF file format is that you can specify exact colors to use in your artwork after the artwork is created. The catch is that you can only choose from the 256 colors that the GIF format supports. (Other formats, such as RGB support up to 16.7 million colors. Yikes!) So how do you get 216 out of 256? Well, unfortunately, only 216 colors actually display the same on all Web browsers and computer platforms. That’s what makes them Web safe.

What happens if you use a color outside of those 216? Whenever a computer encounters a color it can’t display, it dithers the colors. The computer takes the colors that it can display and tries to emulate the missing color, putting alternating squares close together of the colors that it can display. If you look at the monitor from a distance and squint, you see a color that looks very similar to your original color.

Dithering is especially noticeable in large areas of solid color. The effects vary from computer to computer and browser to browser. Sometimes the effects aren’t noticeable at all. Sometimes you get an obvious plaid or striped pattern. Other times, you get plaids and stripes together (and that is such a fashion faux pas).

| Remember? |

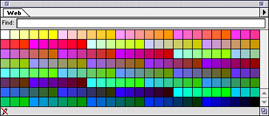

Bottom line: If it’s critical that your colors display consistently (and without dithering) to as many viewers as possible (as in the case of a corporate logo on a home page), use Web-safe colors. Use these Web-safe colors when you save your Illustrator graphic for the Web or when you first create your graphic in Illustrator. You can change the colors in your previously created Illustrator artwork by choosing File→Save for Web. Or you can start out using Web-safe colors to build your artwork (which may save some hassle down the line) by choosing Window→Swatch Libraries→Web. The Web color palette is shown in Figure 16-1.

Figure 16-1: The Illustrator Web color palette. |

Just click any color in this palette and add it to your Swatches palette so that you can use it just as you do any other color. If you use colors only from this palette, you ensure that your artwork uses only Web-safe colors. However, many Illustrator features (such as blends, color filters, and transparencies) can quickly turn even these colors into unsafe colors. Illustrator likes millions and millions of colors. . . .

Don’t let all this talk of Web-safe colors make you gun-shy. In some situations, Web-safe colors are vital (for example, in logos and large on-screen areas of solid color) — in other situations, they just don’t matter. Dithering is most obvious in large areas of solid color; if your graphic is made up of many small parts, the dithering won’t really be noticeable.

| Tip? |

The Save for Web command enables you to decide at any time whether to use Web-safe colors when you save your illustration (See the section later in this chapter, “Creating Web-Specific Pixel Graphics.”) |

Working in Pixel Preview mode

The majority of graphics created for the Web are pixel-based. The two most widely supported graphics file formats on the Web are JPEG and GIF, and these formats save only pixel data, not vector data. (See Chapter 2.) When your graphics are in either of these formats, the majority of Internet users will be able to view your graphics. Fortunately, Illustrator can save graphics as both JPEGs and GIFs. Because pixel-based and vector-based images can look quite different, Illustrator has a special preview mode designed for when you’re creating graphics for the Web: Pixel Preview mode. In Pixel Preview mode, you can see what your vector artwork will look like when it’s turned into pixels for display on the Web. That way, you get a better idea of what the final artwork will look like on the Web (rather than waiting to be surprised when you see it in the browser for the first time).

To turn on Pixel Preview mode, choose View→Pixel Preview. You may not notice anything different on-screen until you zoom in closer than 100%. Try 200% to really see the pixel detail. Figure 16-2 shows Pixel Preview turned off and turned on at 200%.

Figure 16-2: Pixel Preview turned off (left) versus Pixel Preview turned on (right).

This approach is much more convenient than using the File→Save for Web command to convert your graphic into pixels to see how it will look, and then having to resave it if it looks awful. With Pixel Preview mode, you can edit the graphics “live” while you’re viewing the pixels.

Choosing a file format

Deciding what file format to use is almost as perplexing as picking between paper and plastic in the checkout line. Annoyingly, no single correct answer exists when you have to decide which file format to use for the Web. What works best for your purpose normally turns out to be a compromise between what you want and what you can have.

Well, okay, what can you have? You can use any of five file formats to put your graphics on the Web: GIF, JPEG, PNG, Flash (SWF), and SVG. The basic difference is in how each format presents your artwork. Consider this thumbnail comparison:

-

GIF, JPEG, and PNG require that vector-based files be converted to pixel-based artwork. The results look sketchier but load faster.

-

Flash (SWF) and SVG preserve the paths you create in Illustrator — though sometimes they come with gigantic file sizes.

Each format has unique benefits and drawbacks. And here they come now.

GIF file format

GIF is a great format for traditional Illustrator graphics — which means almost no gradients, blends, or fine details. GIF (Graphics Interchange Format) uses a maximum of 256 colors, but typically you want to use even fewer. The fewer colors you use, the smaller your files.

GIF works best with simple graphics that have large areas of solid color. GIF compression encodes an area of solid color as if it were one big pixel. The more solid colors you have (almost regardless of how much on-screen area they cover), the smaller the file size. But if you use gradients, soft drop shadows, or really complex graphics, you introduce more instructions into the file, and the file gets a lot bigger.

In the process of compressing all the different colors in your image (sometimes thousands or millions) down to 256 or fewer, you can get banding and dithering. Banding happens when a range of different colors gets compressed into one solid color and looks like a big stripe in your image where you didn’t intend to put one. Dithering is Illustrator’s way of simulating missing colors by putting tiny squares of the remaining colors close together. This type of dithering is separate from any additional dithering that happens when you don’t use Web-safe colors; see the previous section, “Using Web colors only.”

GIF files differ from JPEG files in two important ways: They can have transparent areas, and you can specify the exact colors you want (such as Web-safe colors) when you save the file.

| Remember? |

GIF is one of the most widely recognized graphics formats for the Web. If you use a GIF file, you virtually guarantee that all your site’s visitors can open it in their browsers. |

JPEG file format

JPEG is among the most widely recognized graphics formats for the Web. Anything that you save in JPEG format can be viewed by almost everyone. The JPEG format (created by the Joint Photographic Experts Group) provides the best compression possible for digitized photographs by throwing information away. Don’t fret too much about this situation. JPEG does so intelligently — examining the image and removing data where the human eye is least likely to notice the absence. What this amazing feat of mathematics means to you as an artist, however, is that your graphics files should start out with a lot of information — so that if you have to throw out a lot of the information, you still have a lot left. Unlike GIFs, JPEGs can’t have transparent areas and offer no way to specify exact colors.

| Tip? |

Complex images with lots of gradients, blends, and soft shadows make good JPEGs. Alas, this format is really lousy for graphics that have big areas of solid color. You can’t hide the loss of information. Basically, if the image looks good as a GIF, it may look bad as a JPEG — and vice versa. Fortunately, you can decide which format works best by using the Save for Web command. |

PNG file format

PNG (Portable Network Graphics) format has a split personality — PNG-8 and PNG-24. The graphics quality that you can get with simple GIFs is also available with PNG-8 graphics. PNG-24, on the other hand, is as adept at handling complex images as JPEG. PNG-8 and PNG-24 files can have transparent areas — and PNG-24 compression is lossless, which means no reduction in image quality.

Why don’t you just use PNG for everything? Well, first, PNG offers no way to control how much compression is applied to the image; you can’t make the image smaller (as you can with a JPEG). More importantly, PNG is not as universal as JPEG and GIF; you don’t see PNG format nearly as often on the Web. If you use this format, not all your visitors can view the graphic on their browsers. Some may need to install a special piece of software called a plug-in so their browsers can read PNG graphics. This situation creates enough hassle that some visitors turn away from Web pages using PNG graphics to avoid downloading and installing the PNG plug-in.

| Tip? |

If your primary concern is image quality, use PNG-24. If you want the maximum number of people to view your work on the Web and the maximum control over file size, use GIF or JPEG. |

Macromedia Flash (SWF) file format

The Macromedia Flash (or SWF) file format, created by Macromedia, is one of the cooler things to happen on the Web in recent years. Flash is the current standard for vector graphics on the Web. Not only does it support vector-based graphics, but it also supports animation, sound, and interactivity. Of course (as per Murphy’s Law of Innovation), something so cool can’t be perfect, and Flash has its blemishes, too. First, nearly every browser requires a plug-in to view a Flash file, which limits your audience from the start. Second, Flash doesn’t support cool Illustrator features, such as transparency, object blends, and gradient meshes. Last, Flash files don’t play well with others. If you try to tie the Flash files into other non-Flash aspects of your Web site, you may run into difficulty.

SVG file format

SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics) format is the upcoming standard for vector graphics. It’s the coolest thing that will happen to the Web in the near future — which means that you still have a while to wait. As with Flash graphics, the current versions of most browsers need a plug-in in order to be able to read SVG files.

Ah, but the upside is tantalizing. SVG supports anything that you can create in Illustrator, as well as animation and interactivity. SVG files can interact with HyperText Markup Language (HTML) pages and work in conjunction with eXtensible Markup Language (XML)-driven Web sites. A long list of companies, including Adobe and Corel, are fully behind SVG. It may well become the dominant vector-based graphics format in a few years (perhaps by the time the International Space Station is complete). Watch out for the following pitfalls:

-

I’m waiting: Although the industry has great expectations for SVG by 2005, it may not seize the vector-based graphics crown on schedule.

-

I’m still waiting: Although SVG is one of the coolest formats out there, it has yet to be adopted on a wide scale.

So which file format is best, already?

Sorry, but I can’t tell you which file format is the best choice for you to use. That answer depends on what you need the file format to do and what tradeoffs you’re willing to live with. That’s the most practical answer for now. However, a summary may help ward off the Too-Many-Choices headache, so here goes:

-

Maximum compatibility: Use GIFs and JPEGs if you want maximum compatibility with as many people as possible.

-

Simplicity: Use GIFs for simple graphics with large, solid colors or for transparency.

-

Complexity: Use JPEGs for more complex graphics with gradients and so forth.

-

Maximum quality: Use PNG for maximum-quality complex graphics when compatibility isn’t an issue.

-

Web considerations: Use Flash when you need to publish vector-based graphics on the Web and want as much compatibility as possible (but don’t require as much compatibility as with GIFs and JPEGs).

-

La vida loca: Use SVG when you want as many bells and whistles as possible and are willing to throw compatibility to the wind.

If we’re all lucky, everyone will eventually adopt SVG as the standard, and we won’t have to worry about issues, such as which file format to use. (Of course, you gotta ask yourself: Do I feel lucky?) Until then, choosing the right file format is a juggling act that balances features, quality, and compatibility.